An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (Phil Nibbelink & Simon Wells, 1991): I concede my interest didn’t stray too far from the knowledge that Fievel Goes West offers the final film role of the immortal Jimmy Stewart, or that it co-stars John Cleese. But my girlfriend likes the American Tail series, namely the first and second, so here were are. And they’re not bad: Fievel Goes West is an odd amalgam of Jewish-Russian stereotypes and cowboy culture, throwing in some New York gangsters and high-society Britishisms to boot, but maybe that’s the intention of this all-American melting pot. It sort of works. Had the writers any real sense of flow, and were they able to string together the adventure story with more substantial (or at least emotional) dialogue, perhaps by focusing on any single character’s depth at all, this could’ve been a very successful film. As it stands, it is a mishmash of one-off jokes and oddball characters, brought to life by the beautifully talented voice actors and mostly endearing songs.

An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (Phil Nibbelink & Simon Wells, 1991): I concede my interest didn’t stray too far from the knowledge that Fievel Goes West offers the final film role of the immortal Jimmy Stewart, or that it co-stars John Cleese. But my girlfriend likes the American Tail series, namely the first and second, so here were are. And they’re not bad: Fievel Goes West is an odd amalgam of Jewish-Russian stereotypes and cowboy culture, throwing in some New York gangsters and high-society Britishisms to boot, but maybe that’s the intention of this all-American melting pot. It sort of works. Had the writers any real sense of flow, and were they able to string together the adventure story with more substantial (or at least emotional) dialogue, perhaps by focusing on any single character’s depth at all, this could’ve been a very successful film. As it stands, it is a mishmash of one-off jokes and oddball characters, brought to life by the beautifully talented voice actors and mostly endearing songs.

Julie & Julia (Nora Ephron, 2009): There’s a reason that Julie & Julia, Nora Ephron‘s final film, is so rarely talked about outside the context of Meryl Streep’s many transformational roles. But its not entirely fair. If Streep were not cast, the film would have received much less attention, but every reviewer would have highlighted Amy Adams’s adorable neurotic mannerisms, or the script’s clever and strikingly contemporary feminist context, which pits the two ever-supportive husbands in the kind of role too often reserved for supporting female actors, names billed under the manly male counterpart. It’s oddly refreshing. Apologies here, but I’m a guy, and so the husbands’ total characterlessness outside of their wives plots stuck out to me almost as much as the delicious food. On that note: Don’t watch this movie on an empty stomach.

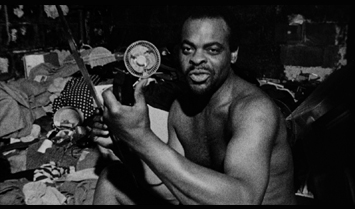

Dark Days (Marc Singer, 2000): Dark Days is technically a documentary, but falls into that sub-category of advocacy film (The Cove, etc.) that affects its subjects as much as it documents them. One-time director Marc Singer delved into New York’s cavernous underground for two years to film the breathtaking life of the city’s daring homeless who made their own home in the tunnels among the subway lines. Among the more astonishing realizations: Homeless eat way better than one might expect (one man is shocked to see his friend crack an egg to make mix into patties set on the stove; we see another actively rejecting food he doesn’t recognize, rewriting the apparently inaccurate adage that beggars can’t be choosers); their makeshift homes are so well built that they themselves are surprised when they have trouble tearing them down; and many of them, despite being recovering or current addicts, are rather articulate. What is not mentioned in the film, but changes one’s perspective on the whole thing, is that the involvement of the Coalition for the Homeless was directly instigated by Singer. He forged his own movie’s reality. Some documentary critics might call this disingenuous filmmaking, but his subjects, and certainly his film, are better off for it. By the end of the modest 80-minute runtime, I challenge a soul to not feel lucky for the house and wealth they were born into.

Dark Days (Marc Singer, 2000): Dark Days is technically a documentary, but falls into that sub-category of advocacy film (The Cove, etc.) that affects its subjects as much as it documents them. One-time director Marc Singer delved into New York’s cavernous underground for two years to film the breathtaking life of the city’s daring homeless who made their own home in the tunnels among the subway lines. Among the more astonishing realizations: Homeless eat way better than one might expect (one man is shocked to see his friend crack an egg to make mix into patties set on the stove; we see another actively rejecting food he doesn’t recognize, rewriting the apparently inaccurate adage that beggars can’t be choosers); their makeshift homes are so well built that they themselves are surprised when they have trouble tearing them down; and many of them, despite being recovering or current addicts, are rather articulate. What is not mentioned in the film, but changes one’s perspective on the whole thing, is that the involvement of the Coalition for the Homeless was directly instigated by Singer. He forged his own movie’s reality. Some documentary critics might call this disingenuous filmmaking, but his subjects, and certainly his film, are better off for it. By the end of the modest 80-minute runtime, I challenge a soul to not feel lucky for the house and wealth they were born into.

The Queen of Versailles (Lauren Greenfield, 2012): This film could not have been successful without the rise of reality television, which, in a way, sort of justifies reality TV’s existence. The Queen of Versailles uses many of the same shlocky tropes as the much-despised TV genre; namely, making the audience feel mentally and emotionally superior to the idiots onscreen, who are so divorced from reality, from their emotions and the world around them that, in the case of the Queen herself, trophy wife Jacqueline Siegel (whose boobs are so disgustingly huge and fake that it borders on constant distraction), she tells the director plainly that she’ll have to watch the movie to find out what’s going on in her life. The first act takes an abrupt drop when the housing bubble crash destroyed the economy, and the husband, David Siegel (for whom we feel almost pity so far, as we watch him balance his wife’s spending habits with his concept of an ideal rich-man’s life), becomes a menacing, solitary figure, alienating himself from his family with repeated scorn and detachment. Suddenly, the wife doesn’t seem like such a bad person. Though the doc would have benefited immensely from being more plot-driven — perhaps owing to the fact that Mr. Siegel likely didn’t want them too close to his work, which is largely shrouded in complicated-sounding mystery — it’s at least an amusing trip through a hallucinated, blown-up version of the American Dream.

The Queen of Versailles (Lauren Greenfield, 2012): This film could not have been successful without the rise of reality television, which, in a way, sort of justifies reality TV’s existence. The Queen of Versailles uses many of the same shlocky tropes as the much-despised TV genre; namely, making the audience feel mentally and emotionally superior to the idiots onscreen, who are so divorced from reality, from their emotions and the world around them that, in the case of the Queen herself, trophy wife Jacqueline Siegel (whose boobs are so disgustingly huge and fake that it borders on constant distraction), she tells the director plainly that she’ll have to watch the movie to find out what’s going on in her life. The first act takes an abrupt drop when the housing bubble crash destroyed the economy, and the husband, David Siegel (for whom we feel almost pity so far, as we watch him balance his wife’s spending habits with his concept of an ideal rich-man’s life), becomes a menacing, solitary figure, alienating himself from his family with repeated scorn and detachment. Suddenly, the wife doesn’t seem like such a bad person. Though the doc would have benefited immensely from being more plot-driven — perhaps owing to the fact that Mr. Siegel likely didn’t want them too close to his work, which is largely shrouded in complicated-sounding mystery — it’s at least an amusing trip through a hallucinated, blown-up version of the American Dream.

Senna (Asaf Kapadia, 2010): The months it must have taken to find all the footage to make Senna, the delicate 104-minute portrait of infamous Brazilian Formula 1 racer Ayrtron Senna, is daunting just to consider. What the doc develops in exhaustive stock footage, though, it lacks in narrative context; as someone who doesn’t especially care about cars, repeated unexplained details (I still don’t know exactly what a “pole position” is or how one is determined) yank one out of the story as often as the terrific scene-setting draws one in. Senna himself is a fascinating character to observe, to watch him grow from a boyishly good-looking go-kart racer to a solemn, sometimes depressed adult in competition with his devilishly clever rivals, his emotions as fragile as the cars themselves. We know how the movie ends — he famously dies in a crash at age 34 — but we never know quite how or when it will happen, which keep the last act nail-bitingly alive until the credits roll.

Senna (Asaf Kapadia, 2010): The months it must have taken to find all the footage to make Senna, the delicate 104-minute portrait of infamous Brazilian Formula 1 racer Ayrtron Senna, is daunting just to consider. What the doc develops in exhaustive stock footage, though, it lacks in narrative context; as someone who doesn’t especially care about cars, repeated unexplained details (I still don’t know exactly what a “pole position” is or how one is determined) yank one out of the story as often as the terrific scene-setting draws one in. Senna himself is a fascinating character to observe, to watch him grow from a boyishly good-looking go-kart racer to a solemn, sometimes depressed adult in competition with his devilishly clever rivals, his emotions as fragile as the cars themselves. We know how the movie ends — he famously dies in a crash at age 34 — but we never know quite how or when it will happen, which keep the last act nail-bitingly alive until the credits roll.